|

The design tricks keeping your kids hooked on games and apps – and 3 things you can do about it, Chris Zomer, Deakin University and Sumudu Mallawaarachchi, University of Wollongong

This article is part of a series on the great internet letdown. Read the rest of the series. Ever found yourself unable to resist checking out a social media notification? Or sending a random picture just to keep a Snapchat “streak” going? Or simply getting stuck staring at YouTube because it auto-played yet another cute cat video? If so, you’re far from alone. And if we adults can’t resist such digital temptations, how can we expect children to do any better? Many digital environments are not designed with the best interest of users in mind – and this is especially true of games, apps and platforms commonly used by kids and teens. Designers use persuasive design techniques to make users spend more time on apps or platforms, so they can make more money selling ads. Below, we explain some of the most common design tricks used in popular games, social media and apps. Decision-making made easy 🔀Social media and streaming platforms strive to provide “seamless” user experiences. This makes it easy to stay engaged without needing to click anything very often, which also minimises any obvious opportunities where we might disengage. These seamless experiences include things such as auto-play when streaming videos, or “infinite scrolling” on social media. When algorithms present us with a steady flow of content, shaped by what we have liked or engaged with in the past, we must put in extra effort to stop watching. Unsurprisingly, we often decide to stay put. Rewards and dopamine hits 🧠Another way to keep children engaged is by using rewards, such as stars, diamonds, stickers, badges or other “points” in children’s apps. “Likes” on social media are no different. Rewards trigger the release of a chemical in our brains – dopamine – which not only makes us feel good but also leaves us wanting more. Rewards can be used to promote good behaviour, but not always. In some children’s apps, rewards are doubled if users watch advertisements. Loot boxes and ‘gambling’ 💰Variable rewards have been found to be especially effective. When you do not know when you will get a certain reward or desired item, you are more likely to keep going. In games, variable rewards can often be found (or purchased) in the form of “loot boxes”. Loot boxes might be chests, treasures, or stacks of cards containing a random reward. Because of the unpredictable reward, some researchers have described loot boxes as akin to gambling, even though the games do not always involve real money. Sometimes in-game currency (fake game money) can be bought with real money and used to “gamble” for rare characters and special items. This is very tempting for young people. In one of our (as yet unpublished) studies, a 12-year-old student admitted to spending several hundred dollars to obtain a desired character in the popular game Genshin Impact. The lure of streaks 🔥Another problematic way of using rewards in design is negative reinforcement. For instance, when you are at risk of a negative outcome (like losing something good), you feel compelled to continue a particular behaviour. “Streaks” work like this. If you do not do the same task for several days in a row, you will not get the extra rewards promised. Language learning app DuoLingo uses streaks, but so does Snapchat, a popular social media app. Research has shown a correlation between Snapchat streaks and problematic smartphone use among teens. Streaks can also make money for apps directly. If you miss a day and lose your streak, you can often pay to restore it. Loss of reputation 👎Reputation is important on social media. Think of the number of Facebook friends you have, or the number of likes your post receives. Sometimes designers build on our fear of losing our reputation. For instance, they can do this by adding a leaderboard that ranks users based on their score. While you may have heard of the use of leaderboards in games, they are also common in popular educational apps such as Kahoot! or Education Perfect. Leaderboards introduce an element of competition that many students enjoy. However, for some this competition has negative consequences – especially for those languishing low in the ranks. Similarly, Snapchat has a SnapScore where reputational loss is still at play. You do not want a lower score than your friends! This makes you want to keep using the app. Exploiting feelings of connection 🥰Another tool in the designers’ bag of tricks is capitalising on the emotional ties or connections users form with influencers or celebrities on social media, or favourite media characters (such as Elmo or Peppa pig) for younger children. While these connections can foster a sense of belonging, they can also be exploited for commercial gain, such as when influencers promote commercial products, or characters urge in-app purchases. What can parents do? 🤷Persuasive design isn’t inherently bad. Users want apps and games to be engaging, like we do for movies or TV shows. However, some design “tricks” simply serve commercial interests, often at the expense of users’ wellbeing. It is not all bleak, though. Here are a few steps parents can take to help kids stay on top of the apps:

For the moment, the responsibility for managing children’s interactions with the digital realm falls largely on individuals and families. Some governments are beginning to take action, but measures such as blanket age-based bans on social media or other platforms will only shield children temporarily. A better approach for governments and regulators would be to focus on safety by design: the idea that the safety and rights of users should be the starting point of any app, product or service, rather than an afterthought. Chris Zomer, Associate Research Fellow at the Centre of the Digital Child, Deakin University and Sumudu Mallawaarachchi, Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child, University of Wollongong This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

All work, all play: the art of videogame writing (2026-02-26T11:31:00+05:30)

Scott Knight, Bond UniversityGames writers dream up characters, dialogue, motivations and plot much like film screenwriters. But rather than keeping an audience captive for two or three hours at a time as in cinema, gamers will play for dozens if not hundreds of hours over the course of a game. While some factors of screenwriting come into play in videogames, the nature of game storytelling is quite different. This is the theme being explored at Perth Festival this weekend in The Game Changers: The Writer and The Game, which on the face of it seems to break the traditional model for writers festivals. So what can we say about writing for games? Player agencyAt the heart of game storytelling is the concept of “player agency”. Here, “agency” refers to the ability of a player to make changes within the game environment, or even more importantly, the illusion of being able to do this. If the game presents a convincing enough illusion of freedom then the player suspends his or her disbelief in the artificiality of the game’s world and the limitations in their choice of pathway. As a medium of interaction, videogames present the player with different possibilities and ask them to enact stories based on designed structures. This may take a linear form, as in the clearly defined pathways of the action-adventure The Last of Us (2011), to the relatively non-linear in the sense of freedom experienced playing game Skyrim (2011). Videogames run a broad spectrum and, while it is accepted that all games have rules, it can be argued that videogames are not necessarily a story-based medium. Looking to early game history, game spaces were more akin to game boards or sports fields. Think of maze games such as Pac-Man (1980), sports games such as Horace Goes Skiing (1982), and tower defence games such as Plants vs Zombies (2013). The objectives of these types of games are straightforward – stay alive as long as possible, and/or obtain a high score. The game space may be limited but the play strategies are endless. Story may be ascribed to these types of games, but they aren’t considered story-based games in a significant sense. Narrative evolutionAs game history progressed, the abstraction of games like Pac-Man evolved into the “convincing illusion” of fictional game worlds. The advent of navigating 3D space in games from the mid-1990s such as Super Mario 64 (1996) and Tomb Raider (1996) led to the living, breathing worlds we experience in games such as Skyrim (2011) and Grand Theft Auto V (2013). Over the last ten years, game storytelling has made significant developments along with the rapid rise in new capabilities of each subsequent console generation. Building on this, the flourishing of the indie game movement has led to an increased experimentation and sophistication in game form and storytelling. We now see a greater range of subject matter and variety of storytelling approaches from both mainstream and indie game development, from the emotional drama of Heavy Rain (2010) to the pixelated puzzles of Fez (2012) and the simple ethereal serenity of Journey (2012). With the further maturation of videogames as a form of expression, and the average age of gamers being over 30 in countries such as Australia, game developers have greater remit to create and explore more adult-orientated experiences. Contemporary videogame experiences can be so emotional and encompassing that players are moved deeply while playing certain games – think of the harrowing decision-making of The Walking Dead (2012) or the relationship that develops between Joel and Ellie in The Last of Us (2011). American media scholar Henry Jenkins argues that games use their environment to tell stories and may exhibit four dimensions of what he calls “narrative architecture”: games may draw upon pre-existing stories and enact story through traditions drawn from other media such as cinema in the form of non-interactive expository scenes or “cut scenes”, embed story elements within the game space, and create the possibility for players to author their own stories by constructing the world in which they play as in the case of Minecraft (2011). Exploring human emotionIn Braid (2008), game creator Jonathan Blow set out to explore loss and forgiveness. A game “mechanic” is a feature that describes how the game behaves or operates. It is tied in to the game’s rules and what a player can do within the game. Braid is a puzzle game in which the core mechanic is the player’s ability to manipulate the flow of time, including rewinding time. Here the central thematic and conceptual concerns of the game are designed into a gameplay feature that explores memory and the feelings associated with failed relationships. A game such as Gone Home (2013) demonstrates environmental storytelling. In it, the player assumes the role of Katie, who returns home from a long trip overseas to her empty family home and discovers a mysterious note written by her sister, Samantha. A liminal example of game design as exploration, Gone Home is akin to a detective story, in which the player searches the house for artefacts that develop the tapestry of the intriguing narrative about Samantha and the rest of the Katie’s family. The accomplishment in the writing of Gone Home can be seen in the way the game activates players’ curiosity to draw them into the mystery. There’s a subtlety and elegance to the writing of this game – despite not encountering any other physical characters, fragments of narrative are dispersed and embedded throughout which the player must actively piece together to interpret the story. In many ways, the similarities between the game writing and screenwriting processes are limited to constructing overarching plots or writing character dialogue and cut scenes – should these techniques even be employed in the game’s approach to story. Videogames are designed and programmed for action, which means storytelling has the capacity to be complex and engaging in ways not possible in other media. Story is affected on a moment-to-moment basis dependent on the affordances employed, the way spaces are navigated, or choices the player makes. Videogame environments create a world for meaningful play where events unfold, challenges evolve and the story is different for each and every player. The Game Changers: The Writer and The Game takes place on Saturday February 22 at Octagon Theatre, University of Western Australia. Perth International Arts Festival runs until March 1. Scott Knight, Assistant Professor of Film, Television and Videogames , Bond University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Computer Games Improve Neuroplasticity After Traumatic Brain Injury (2026-02-20T12:21:00+05:30)

Credit: Axeville/ Unsplash. Patients with traumatic brain injuries who complete computerized cognitive games show improved neuroplasticity. Original story from New York University Patients with traumatic brain injuries (TBI) who complete computerized cognitive games show improved neuroplasticity and cognitive performance, according to new research published in Journal of Neurotrauma. Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change and reorganize nerve fibers that are responsible for learning and processing. The nerve fibers facilitate communication among neurons for functions including speech, memory, and problem solving. In a healthy brain, there are myriad bundles of strong nerve fibers for these functions, but in an injured brain, these fibers can be damaged and the connections can be reduced (similar to telephone wires after a heavy storm). The researchers' findings offer new insight into the brain's resilience and ability to repair itself. “This study demonstrates changes in the brain’s white matter and shows that computerized cognitive remediation in adults with chronic brain injury can induce neuroplasticity. It builds on our earlier studies showing how these computer games can improve cognition as well as change the connections between brain regions and the structure of the pathways that connect the brain regions,” says senior author Gerald Voelbel, associate professor of cognitive neuroscience at NYU Steinhardt. Researchers randomly assigned 17 adults (ages 24-56) with chronic TBI to either an experimental group that played computer games or the control group. The experimental group used the Brain Fitness Program 2.0, a computer program with cognitive games that include recalling syllable sequences, distinguishing between different sound frequencies, and recalling details from a verbal story. Participants completed 40 one-hour sessions over 14 weeks. Using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging, which measures the speed and direction of water molecules traveling through the brain, the researchers found that participants who completed the games saw significant changes in neuroplasticity over time compared to the group that did not complete them. These changes were related to improvements on objective measures of participants’ processing speed, attention, and working memory. “This study reveals that the changes in the nerve fibers, such as increased strength and stability, were related to the improved cognitive ability in adults with a chronic brain injury,” says Voelbel. “This provides great evidence that the brain can change over time, even in people with a brain injury, with computer exercises that improve cognitive abilities.” Reference: Voelbel HML, Rath JF, Bushnik T, Flanagan S, Lazar M, Gerald T. Computerized Cognitive Remediation Affects White Matter Microstructure in Relation to Improved Cognitive Function in Adults with Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2026. doi: 10.1177/08977151251414085 This article has been republished from the following materials. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source. Our press release publishing policy can be accessed here. Computer Games Improve Neuroplasticity After Traumatic Brain Injury | Technology Networks

|

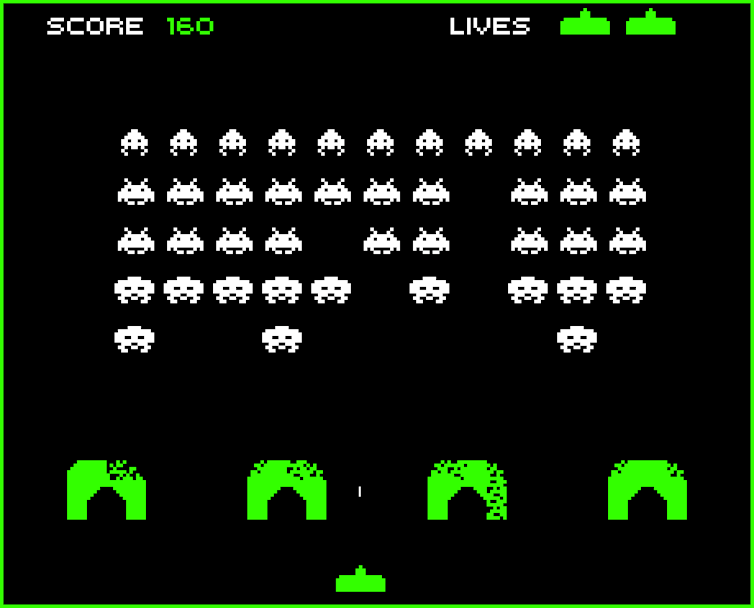

What 40 years of ‘Space Invaders’ says about the 1970s – and today (2026-02-16T13:08:00+05:30)

The iconic shooting game in its original stand-up arcade form. Jordiferrer, CC BY-SA

Lindsay Grace, American University School of Communication The iconic shooting game in its original stand-up arcade form. Jordiferrer, CC BY-SA

Lindsay Grace, American University School of CommunicationThe “Space Invaders” arcade video game, celebrating its 40th anniversary, is an iconic piece of software, credited as one of the earliest digital shooting games. Like many early games, it and its surrounding myths showcase the cultural collisions and issues current at its creation by Japanese game designer Tomohiro Nishikado. As a game designer and teacher of games, I know how meaning is carried from designer to the mechanics of play. As a game studies researcher, I also know how games reveal myth, meaning and culture. An analysis of “Pac-Man,” for instance, shows how that game embodies many values of its day – including consumerism, drug use and gender politics. The message in “Space Invaders” is as basic as the graphics: When faced with conflict, players have no option except to blast it away. Avoiding an enemy only delays the inevitable; players cannot move forward or back, but can only defend their space. There’s not even a reason why the invasion is occurring. Players know only that the invaders must be destroyed. It’s a distinct cultural perspective, emphasizing shooting over everything else. A historical pioneerThe history of many shooting games can be traced to “Space Invaders.” It’s not the first – MIT’s “Spacewar!” was earlier, in 1961 – but “Space Invaders” is among the most copied. Even people who never played the original “Space Invaders” have likely played the more than 100 clones of it – including the first advertising game, “Pepsi Invaders.” The release of “Space Invaders” foreshadowed the growth of the Japanese games industry, which itself was seen as a fearsome cultural invasion of the U.S. by Japan. The tension was expressed in popular media as a defense of American individualism against the power and efficacy of Japanese collectivism and corporate culture. This tension displayed itself in popular media like the comedy film “Gung Ho” as a combined Japanophobia and Japanophilia. “Space Invaders” also highlighted how tenuous some elements of Western identity were. The U.S. had built its sense of self on being the greatest, but was being challenged by Japanese economic growth. But it was complicated: As Japanese automakers won customers from the American car companies, they began to build their cars in the U.S. – so were they Japanese or American cars? In the same way, if the American game maker Atari’s biggest hit was a Japanese-made game, how American was Atari’s success? In any case, millions of U.S. consumers bought the Atari 2600 game system to be able to play the hit arcade game “Space Invaders” at home. Five years later, in 1983, the games industry crumbled in large part because American-made games were not interesting and too similar to each other. In 1985 the Japanese-made Nintendo Entertainment System ushered in a new era of home console play. That continued the challenge to the American identity: U.S. companies failed to innovate and lead, and a Japanese company filled the innovation void. The myths of (space) invasion“Space Invaders” also has collected some myths around it, which reveal more about society than about the game itself. The most notable legend is that “Space Invaders” was so popular that the Japanese economy ran out of the coins needed to play it in arcades. It’s not true, but like many myths about games, both positive and negative, it sounds so good it’s easy to champion anyway. That fable is a prequel to larger popular fictions about games. People blame games for the decline of economies and for joblessness. The innovations created in games support technological innovations that change society and the way people socialize, yet people are also eager to blame large systemic issues like gun violence in schools on video games. Another tale is that “Space Invaders” demand was so strong that even with multiple game machines installed, there were lines to play. Whether or not they were queuing up for their own turns, it’s definitely true that people watched others play. That helped set the stage for the growth of arcades and LAN-gaming parties, precursors to professional players and today’s multi-billion-dollar industry of e-sports. History shows that games change society, pointing it toward play and creating new economies. The advent of arcades was as novel as the contemporary use of the micro-transactions common in mobile games now. Their incubation of community and spectator play spawned countless YouTube gaming channels. Like the space invaders that descend on the player, unknown but always threatening, games scare some people. They seem to be unrelentingly approaching, different and hard to keep pace with. Games challenge players to adapt and dismantle the conventions under which people hide. But, like playing “Space Invaders” itself, the joy comes in interacting with that change, mastering it and moving on to the next level. Lindsay Grace, Associate Professor of Communication; Director, American University Game Lab and Studio, American University School of Communication This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Online gaming communities could provide a lifeline for isolated young men (2026-02-16T13:07:00+05:30)

Tyler Prochnow, Texas A&M UniversityOnline gaming communities could be a vital lifeline for young men struggling silently with mental health issues, according to new research. My colleagues and I analyzed an all-male online football gaming community over the course of a year. We discovered that members who reported more depressive symptoms and less real-life support were roughly 40% more likely to form and maintain social ties with fellow gamers compared with those reporting more real-life support. This finding suggests the chat and community features of online games might provide isolated young men an anonymous “third place” – or space where people can congregate other than work or home – to open up, find empathy and build crucial social connections they may lack in real life. Why it mattersMental health issues like depression and suicide are on the rise among young men in the U.S., yet social stigmas and traditional masculinity often inhibit them from seeking professional assistance. Up to 75% of people with mental illnesses go without treatment, with men especially unlikely to pursue counseling or therapy. Online social spaces, like gaming communities, may offer an alternative avenue to find connection and discuss serious personal problems without the barriers of formal mental health services. The social features of online games allow players to privately chat and build friendships, potentially creating vital informal support networks. While not a substitute for professional care, these virtual forums could encourage discussion of mental health challenges among young men facing social isolation and untreated depression. More comprehensive research is still needed, but the social features of online games may literally provide young men a lifeline when they have nowhere else to turn. How we do our workWe asked members of a small online gaming community to tell us specifically who in the community they talked to about important life matters. Using an open-ended survey, we then asked about these conversations. We also asked them to report how often they felt certain depressive symptoms, as well as their feelings on in-person and online social support. Several participants specifically said they confided about topics they felt unable to discuss with people in their real lives, suggesting these online friendships provided an outlet they were otherwise lacking. The depth of sharing indicates these online friendships had moved beyond superficial topics into deeper emotional support and bonding. What still isn’t knownOur research was limited to 40 male participants interested in college football video games. Further investigations using larger, more diverse samples across various gaming genres are needed to confirm these preliminary findings. A key question is whether online social support directly improves depression – or are depressed individuals simply more inclined to seek connections virtually? Despite a massive industry and audience for online gaming, its mental health impacts remain murky. What’s nextMy colleagues and I are launching studies that analyze the impact of multiplayer games on teamwork, leadership and social skills in high school and college students compared with traditional extracurricular activities. We are also investigating how involvement in esports can cultivate lasting social relationships and foster a sense of community. Through multiyear studies, we hope to understand online gaming’s risks – alongside its promise for improving mental health, social integration and life skills. The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work. Tyler Prochnow, Assistant Professor of Health Behavior; School of Public Health, Texas A&M University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Are video game developers using AI? Players want to know, but the rules are patchy (2026-02-12T11:14:00+05:30)

|

As with all creative industries, generative artificial intelligence (AI) has been infiltrating video games. Non-generative AI has been in the industry long before things like ChatGPT became household names. Video games would contain AI-driven gameplay systems such as matchmaking, non-player character (NPC) behaviour, or iconic fictional AI characters such as SHODAN and GLaDOS. Now, generative AI is being used to produce game assets and speed up development. This is threatening creative jobs and fuelling worries about low-effort releases or “slop”. If you buy a video game today, you may have no reliable way of knowing whether generative AI was used in any part of its development – from the art and voice work to the code and marketing. Should developers disclose it? Since 2023, AI disclosure in video games has gone from non-existent to patchy. It’s arguably more to do with copyright concerns than being transparent with players. A messy baselineSteam, owned by US video game company Valve, is the largest digital storefront for PC games. It’s also the closest thing to a baseline for AI disclosure – simply because it was the first major platform to formalise a position. Amid the rise of AI in 2023, Valve rejected AI-produced games on Steam, citing legal uncertainty and stating the company was “continuing to learn about AI”. By January 2024, Valve formalised its disclosure rules, requiring developers to declare two categories of AI use: pre-generated content (made during development) and live-generated content (created while the game runs). While industry leaders are optimistic about AI’s role in game development, disclosure remains contentious. Tim Sweeney, chief executive of Steam’s competitor Epic Games, mocked Steam’s AI disclosure in late 2025 as being akin to telling players what shampoo developers use. In recent weeks, Valve has narrowed its disclosure rules, clarifying that developers who submit games to their platform only need to report AI if the output is directly experienced by players. This changes what counts as relevant transparency, effectively giving a green light to AI coding and other behind-the-scenes processes. Valve’s focus on player-facing AI does provide consumers with some transparency and the game submissions are checked before release. However, it’s not clear what happens if the makers of a game don’t disclose AI when they should have. The disclosure system also keeps Steam ahead of a legal grey area regarding copyright and generative AI output. If needed, Valve could quickly pull titles affected by AI copyright claims. Some AI models can memorise copyrighted material and reproduce it when prompted, so this is not an entirely hypothetical scenario. AI disclosure on Steam doesn’t have a consistent format – developers simply have a text field where they can write their disclosure in free form. Since it’s not treated as an official tag, consumers also can’t search or filter for AI content when browsing for games in the store. At the time of writing, a search of SteamDB – a third-party catalogue of Steam’s database – lists more than 15,000 games and software with Steam’s AI disclosure label, with no total count available on Steam itself. In response, user watchdogs have stepped in. The Steam curator group AI Check tracks games with AI-generated assets and flags whether developers disclose AI use – and how. Players are largely in the darkOutside Steam, disclosure is inconsistent if not absent. Indie storefront itch.io provides a searchable “AI Generated” tag, but no disclosure is required on game pages. There’s currently no clear AI disclosure on mobile app stores or console storefronts (Nintendo, PlayStation, Xbox), and they’ve been criticised for letting “AI slop” flood their stores. Epic Games Store and another major distribution platform, GOG.com, also lack clear AI disclosures. GOG recently faced backlash for using AI-generated artwork in its own storefront promotion. All this leaves players in the dark, while developers face backlash for AI use that many consider harmful for the industry. Transparency is importantMany players care about AI use in games and when disclosure is missing. There are plenty of cases in which developers were “caught out” using generative AI and responded with ad hoc statements, asset changes, or even had Game of the Year awards rescinded. But there are also cases in which suspicion has caused cancellations or wrongful accusations of games using AI art when it was actually drawn by a human artist. This is why transparency on AI use is important. Many Australians report low familiarity with AI, and research suggests having more information can shift people’s views, helping people make informed choices and avoid witch hunts. Many people have ethical concerns about AI use, or are worried about environmental consequences due to how many resources the AI data centres chew up. All this means AI disclosure is currently a consumer rights issue, but it’s governed entirely by the platforms where people purchase the games. Players don’t need to know what shampoo a developer uses. But they do deserve a clear view of whether the art was AI-generated, whether writers or voice actors were replaced, and whether a game built on AI-generated code is likely to survive an update. Steam’s disclosure system is a start, but it means little if the information can’t be found or filtered for. Every game storefront should make generative AI use clear at the point of purchase – because players deserve better. Thomas Byers, PhD Candidate & Research Assistant, Faculty of Engineering & IT, The University of Melbourne and Bjorn Nansen, Associate Professor, School of Computing and Information Systems, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

What’s leisure and what’s game addiction in the 21st century? (2026-02-06T11:43:00+05:30)

|

The online world comes with risks – but also friendships and independence for young people with disabilities (2026-02-06T11:42:00+05:30)

Andy Phippen, Bournemouth University and Hayley Henderson, University of Northampton“In the real world, I’m a coward. When I’m online, I’m a hero.” These words, paraphrased from a conversation with a young man with autism, have stayed with us throughout the years of research that underpin our recently published book exploring the relationship between children with special educational needs and disabilities and digital technology. We’re constantly bombarded with warnings about the potential dangers of digital technology, especially for children. But this quote captures something we might miss. The digital world can be a vital space of empowerment and connection. In our work, we’ve found that digital technology offers more than just access to learning for young people with special educational needs and disabilities. It opens doors to social lives, creative outlets and even employment opportunities that might be closed to them in the offline world. And yet, this potential is too often overshadowed by fears about the risks and harms they might encounter online. Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences. Adolescence, the Netflix drama that delves into the hidden dangers of growing up in a digital world, has taken up a lot of the national conversation around social media, cyberbullying and online exploitation. But there is another show on Netflix that has received far less attention. The Remarkable Life of Ibelin is a powerful documentary that tells the story of Mats Steen, a young Norwegian man with a severe disability who found freedom, friendship and purpose in the online world of gaming. Though physically limited by Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Mats, known as “Ibelin” in World of Warcraft, built a rich life online. After his passing at 25, his gaming friends revealed just how much he had meant to them. Some travelled to his funeral. The film challenges stereotypes about online gaming. It shows it as a source of connection, compassion, and real human bonds. We’ve spoken to many young people with special educational needs and disabilities who echo the same themes. Online spaces offer a sense of identity and capability they don’t always feel offline. We found that the benefits of digital engagement for children with special educational needs and disabilities are extensive. It enhances communication: tools such as voice interfaces and text-to-speech software help those with speech or language difficulties express themselves confidently. Online platforms create spaces for friendships, especially for those who find face-to-face interaction challenging. But the digital world isn’t an equal playing field. Children with special educational needs and disabilities face disproportionate levels of online harm, including grooming, cyberbullying and exposure to inappropriate content. Crucially, they often lack the tools or support to report harm or seek help. This, of course, raises concerns for the parents, carers and teachers of young people with special educational needs and disabilities. We’ve found that parents, carers and teachers we’ve spoken to often reach for a “prohibition first” approach – feeling young people will be safer if they do not have the access to the internet and social media that a young person without their needs might enjoy. Safeguarding and empowermentWe’ve been asked questions such as “What apps should I ban?” or “How do I stop my child going on the dark web?” These questions reflect a risk-averse mindset that fails to appreciate the value of digital engagement. Risk cannot be eliminated, but it can be managed. And, more importantly, opportunity must be protected. Too often, safeguarding strategies are done to children, not with them. It’s a good idea for parents and teachers of all children to talk to them about their digital life: what brings them joy, what worries them, where they feel confident or confused. Children are more likely to talk about fears or bad experiences if they feel believed, respected and understood. Make yourself a safe adult to talk to: one who listens without panic. While banning apps or limiting access might be useful in some cases, it should not be the starting point for safeguarding. It’s worth considering whether there are skills that a child could learn that would allow them to use technology safely. What’s more, online safety lessons are best when adapted to the communication style, cognitive ability and emotional maturity of an individual child. Visual aids, social stories, or interactive games may work better than text-heavy advice. Fear can limit what technology can offer the children who may need it most. For young people with special educational needs and disabilities, digital spaces are not simply entertainment, they are platforms for agency, creativity, relationships and voice. The role of adults here is to ensure these spaces are not only safe, but welcoming and empowering. That means moving past automatic restrictions and toward thoughtful, inclusive strategies that support children who might gain the most from using these technologies. We don’t need more bans. We need more belief. Andy Phippen, Professor of IT Ethics and Digital Rights, Bournemouth University and Hayley Henderson, Senior Lecturer in Human Resource Management, University of Northampton This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

‘Stop Killing Games’: Demands for game ownership must also include workers’ rights (2026-01-30T13:37:00+05:30)

With live service games, players are learning that what they’ve really bought is not a game but access to it. And, evidently, that access is something that can be revoked. (Unsplash/Samsung Memory)

Louis-Etienne Dubois, Toronto Metropolitan University and Miikka J. Lehtonen, University of Tokyo With live service games, players are learning that what they’ve really bought is not a game but access to it. And, evidently, that access is something that can be revoked. (Unsplash/Samsung Memory)

Louis-Etienne Dubois, Toronto Metropolitan University and Miikka J. Lehtonen, University of TokyoWhen French video-game publisher Ubisoft announced it was shutting down servers for The Crew, a popular online racing game released in 2014, it wasn’t just the end of a title. It marked the beginning of a broader reckoning about the nature of digital ownership, led by players angry at the company’s decision to deny them something they had paid for. The Stop Killing Games (SKG) movement was born from that moment. As of July 2025, it has gathered more than 1.4 million signatures through the European Citizens’ Initiative. The European Commission is now obliged to respond. At the heart of the issue is a deceptively simple question: when we buy a video game, what are we actually purchasing? For many gamers, the answer used to be obvious. A game was a product, something you owned, kept and could return to at will. However, live service games have changed that dynamic. These are games usually played online with others and that typically require subscriptions or in-game payments to access features or content. They include popular titles such as Fortnite, League of Legends and World of Warcraft. With live service games, players are learning that what they’ve really bought is something more tenuous: access. And, evidently, access is something that can be revoked. Erasing gaming communitiesThe issue goes well beyond The Crew. In the last couple of years alone, several games have been shut down, including Anthem, Concord, Knockout City, Overwatch 1, RedFall and Rumbleverse. There are valid reasons why companies might choose to end support for a title. The game industry is saturated and brutally competitive. Margins are tight, player expectations are high and teams often face impossible deadlines. When an online game underperforms, a publisher will likely be inclined to cut their losses and shut it down. Games tend to accumulate bugs in their code that are complex to clean and create player dissatisfaction. In our research, we have shown that when a game underperforms or becomes too costly to maintain, shutting it down can be a rational, even reparative, decision on many levels. Yet, when companies decide to shut down a live service game’s servers, it’s not just content that vanishes. So do the communities built around it, the digital assets (costumes, weapons and so on) players have earned or paid for and the sometimes hundreds of hours invested in mastering it. In the blink of an eye, the game is gone, often without recourse or compensation. That’s not just a customer service issue; it’s a cultural one. Games are not just another type of software. They are creative works that can foster shared experiences and vibrant communities. Players don’t just consume games, they inhabit them. They trade stories, build friendships and express themselves through digital spaces. Turning those spaces off can feel, to many, like erasing a part of their lives. This profound disconnect between business logic and player experience, which we theorized in the past, is what gave rise to the SKG movement. Video game publishers failed to anticipate the cultural backlash triggered by these shutdowns. What regulators can doThe European Commission’s response to the Stop Killing Games petition could help define the future of digital ownership, cultural preservation and ethical labour in gaming. (Unsplash/Guillaume Périgois) Players of shut-down games may believe they were misled and should be compensated. Unfortunately, the current system offers little transparency and even less protection for them. That’s where regulation can help. The European Commission now has a chance to provide much-needed clarity on what consumers in the European Union are actually buying when they purchase live service games. A good starting point would be requiring companies to disclose whether a purchase grants the buyer ownership or limited access, akin to recent legislation passed in California. Minimum support periods, clearer content road maps (the projected updates) and making companies create mandatory offline versions for discontinued online games might also help prevent misunderstandings. There’s room for creativity here, too. Rather than killing a game outright, companies could allow player communities to take over its maintenance and allow for the continued creation of new content, especially for titles with active fan bases. This is known as “modding,” and in some cases, community-led revivals have even inspired publishers to re-release enhanced editions years later. Developers need protections too Instead of periodically ‘crunching,’ live service game developers are now constantly ‘grinding.’ (Unsplash/Sigmund) Instead of periodically ‘crunching,’ live service game developers are now constantly ‘grinding.’ (Unsplash/Sigmund)There’s another part of this story that’s unfortunately overlooked: the people who make these games. Video game developers are regularly subjected to long hours, poor conditions and toxic workplace cultures in order to meet the demands of continuous live service updates. In our research, we’ve found that this new model of endless content creation and perpetual support is unsustainable, not just financially or technologically, but humanly. Instead of periodically “crunching,” live service game developers are now constantly “grinding.” Somehow, in an industry notoriously demanding for workers, this model has managed to make things even worse. Policymakers need to protect both players and the workers creating games. That means, among other things, rethinking release schedules, enforcing rest periods for development teams and holding companies accountable for the well-being of their staff. The overall health of the industry depends on it. Whether you support the SKG movement or not, the issues it raises are urgent. While the ownership question is a very legitimate one, video game developers deserve more care and protection. The European Commission’s response could help define the future of digital ownership, cultural preservation and ethical labour in gaming. Louis-Etienne Dubois, Associate Professor, School of Creative Industries, The Creative School, Toronto Metropolitan University and Miikka J. Lehtonen, Specially Appointed Associate Professor, College of Business, University of Tokyo This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |